Here’s how to do bean breeding the climate-smart way

‘We need to do “preemptive breeding” if we want to sustain bean production under the more erratic climate of the future’

Photo by Neil Palmer

Projections about the future indicate many parts of the world will see greater heat stress — higher temperatures that can result in more frequent, longer periods of excessive heat for crops. This is bad news for growers of certain crops.

That would include beans, which millions around the globe, especially in Africa and Latin America, consume.

In general, beans, which have three-month growth cycles, can tolerate temperatures up to 23 degrees Celsius at night. Beyond that could mean a disaster: The plants may fail to flower; they may flower, but the pollen can be unviable. Or, they may “abort” or just not fill their pods.

Some places growing beans already experience frequent droughts – up to 80 percent of the time. Currently, dry spells affect the period before harvest or the last month of the bean growth cycle.

But there’s a high likelihood that in 10-30 years’ time, heat stress will become a constraint to bean growing areas, according to previous CIAT research.

“We need to do ‘preemptive breeding’ if we want to sustain bean production under the more erratic climate of the future,” said Dr. Julian Ramirez-Villegas , a climate impacts scientist at CIAT, noting that bean breeding and new bean variety adoption can often take more than a decade.

“We should be thinking about the conditions that farmers are likely to experience and the kinds of new crop traits and varieties that farmers need to be growing for the future and work on those.”

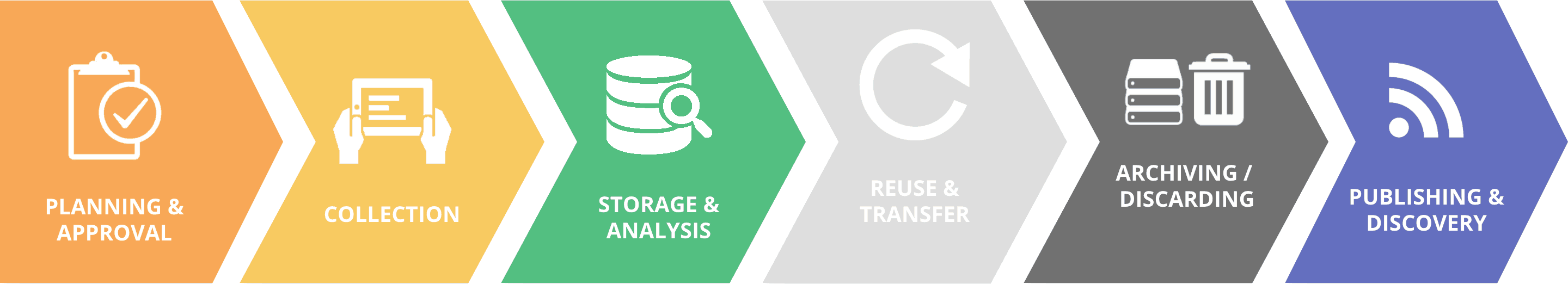

Preemptive breeding entails designing and implementing a strategy to develop crops with traits suited to the conditions expected in the future in a particular area.

CIAT has been doing this for beans: It is breeding beans that can have resistance to possible future viruses.

Breeding beans with heat stress tolerance, though, has been limited.

Photo by Neil Palmer (CIAT). The work of CIAT’s Genetic Resources Unit to regenerate bean seeds, at a field site near Popayan, Colombia.

But having the desired genotypic trait, such as tolerance to heat stress, isn’t enough if the goal is to ensure farmers actually plant any improved crop variety.

Breeding must also address socio-economic aspects of crop variety adoption. In the case of beans, these may include the size of land used for cultivation, and consumer preferences including seed color, size, taste, and the amount of time to cook them.

Last month, Ramirez-Villegas and his team began a study that can guide strategies for breeding heat-tolerant beans. They are collaborating with the CIAT bean breeding program, the University of Leeds and Scotland’ Rural College (SRUC) for this project, which focusses on Colombia.

Beans are a major source of protein for Colombians. And they could become a major source of income for people in areas affected by a 52-year armed conflict, including possibly regions that still grow the illicit coca.

The study aims to determine the different levels of heat stress that various areas in Colombia may endure in the future, the areas that could grow beans under future climate scenarios, and the genotypes or varieties that would suit the conditions of those areas — then feed these data into a model to simulate bean yields under different heat stresses. The project scientists are using freely accessible, interoperable data connected to improved crop modeling tools to create projections that allow breeders make informed decisions.

It will also look into what drives people to plant beans and choose which varieties of the crop to use.

According to Ramirez-Villegas, he and his team have already used such a methodology in a study focused on rice in Brazil.

The goal is, by the end of the yearlong project, to identify areas that can serve as sites to do field trials involving heat stress-tolerant beans.

“We need to be ‘climate-smart’ in many ways,” he said. “If we don’t plan sufficiently ahead for changes that might happen, with new requirements in terms heat stress tolerance or other kinds of plant traits, we’re going to be hardly able to adapt.”

***

Additional information:

The “Bean breeding and adoption in changing climates in post-conflict Colombia” project (BACO)) is a collaboration between CIAT, the University of Leeds, and Scotland’s Rural College. It is funded by the U.K. Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the Newton Caldas Fund, as well as the Community of Practice on Crop Modeling of the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture.

Eliza Villarino

Science Journalist

Cali, Colombia