I want to end malnutrition in Africa. That’s why I’m turning to big data and algorithms.

As an African woman and a nutritionist, there’s nothing more upsetting to me than this fact: Africa is the only region in the world where malnutrition is rising.

Photo by Stephanie Malyon / CIAT

That’s despite the billions of dollars that donors have invested in this continent and the countless interventions, in addition to the commitments made at international summits, to address the problem.

I’ve grown disillusioned about the agendas we set to end malnutrition once and for all. It’s obvious to me that those who made promises to do so have no intention of keeping them.

Take a look at the latest Global Nutrition Report. It says that only 36 percent of the 203 commitments made at the Nutrition for Growth Summit five years ago have been met or on course to be met.

As the report says, “[w]e need to do better” by “ensuring we can hold governments, multilateral agencies, civil society and businesses accountable for delivering their commitments …”

So how can we enable those actors to make good their promises? For my part, it’s research.

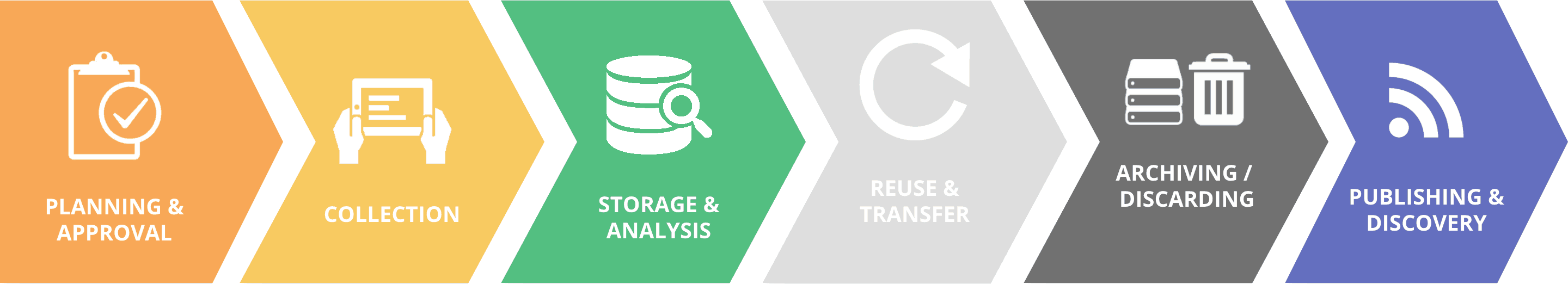

The only way to end malnutrition in Africa is to leave no one behind. To do that, we have to change the way we tackle the problem: We need to stop fighting fires, or taking action only when there’s a crisis, and be more proactive in our approach.

We need to know what works, why does it work, when does it work, and for whom does it work? At the moment, no mechanism exists that can conclusively answer those questions.

So, I, along with colleagues at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture, as well as the African Development Bank, have been pushing for a tool — the Nutrition Early Warning System or NEWS — that can forecast a nutrition problem in Africa such as a famine and sound the alarm early enough so that a crisis won’t have to happen.

NEWS will tap into big data and artificial intelligence (AI) to capture information in the past so we can make the future better.

We’ve seen how big data and AI can have a meaningful impact on agriculture. Our colleagues in Cali have developed climate and agricultural forecasts using big data and AI, which in 2013 helped 170 Colombian rice farmers avoid $3.6 million in losses.

If big data and AI can work for agriculture, why not for nutrition?

Governments and United Nations agencies constantly collect data related to nutrition, and they’re actually well-structured. But often, we don’t really try to understand what the data are telling us.

Perhaps in the past, that’s due to the lack of technology. But now that we have big data and AI, there’s no more excuse.

It’s obvious that there’s important information about nutrition we aren’t capturing or aren’t capturing well.

Take the case of Rwanda for example. In 2016, the rate of children dying during the first 28 days of their lives was 17 out of 1,000. Botswana’s, meanwhile, was 26 out of 1,000. As per the World Bank classification, Rwanda is a low-income country, while Botswana is an upper-middle-income country. That tells me that economic growth alone will not make a difference.

With big data, we will know what the information we have is telling us, and which information we need more or less of.

For NEWS, big data means not only the periodic surveys on nutrition. We’re also exploring using nontraditional data. For instance, algorithms based on social media posts about say a spike in the price or the lack of food can serve as early signals of a future nutrition-related situation.

We also intend to involve communities in this. For the longest time, Africans have depended too much on the government to solve their problems. African communities need to be empowered to resolve their difficulties because history has shown, doing so would lead to less complicated problems. If we want to rid Africa of malnutrition, it cannot be the government’s job alone.

Last year’s famine was, as the United Nations called it, the worst humanitarian crisis since 1945. It’s also the fourth in Africa since the start of the 21st century. A forecast indicates that 5.1 million people in South Sudan might not have sufficient food to eat from January to March 2018. What will happen if there’s a fifth?

Here in Africa, malnutrition means a mother watching her child suffer and having to bury that child because we didn’t know what was happening on time. That’s why we need to change the way we do business around nutrition. We need to look for better ways to save lives. Big data and AI can help.

Mercy Lung’aho

Nutritionist and research scientist at International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT)

Nairobi, Kenya

About the author:

Mercy Lung’aho is a nutritionist and research scientist at the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). Her research includes a landmark study documenting evidence that eating beans biofortified with iron can reduce iron deficiency in women of reproductive age. Her current work is on a Nutrition Early Warning System based on innovative machine learning algorithms that will alert decision-makers to nutrition threats ahead of a crisis and provide options for nutrition interventions and resilience building in national and regional food systems. She holds a PhD in food science and international nutrition from Cornell University, USA.

As rightly said in the article Government can not do all the things, Communities and other stakeholders support is much needed to make

systems like Nutrition Early Warning System {NEWS} work effectively to reach the ultimate goal of ending the malnutrition.

This is a great initiative, and as an animal nutritionist, this inspires and motivates me to learn and engage in big data and AI. I hope you don’t relent in your pursuit. Kudos to you ma.