Beating drought one text at a time

Scientists, meteorologists, start-ups and Microsoft India are coming together to crunch weather data to help farmers beat climate risks and boost yield and profit.

This blog is an effort of the Data-Driven Agronomy Community of Practice to highlight CGIAR’s digital extension work.

Late nights on the family farm are engraved in Anthony Whitbread’s memory.

“I grew up near my grandparent’s farm in a low-rainfall region of Southern Australia. I remember going to their house in the evenings, and having to be very quiet, because they were listening to weather information on the radio,” said Whitbread.

Turning a profit through farming in such conditions is no small feat. Information about what the weather might do is absolutely critical to make the right decisions.

Today, as research director at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Crops (ICRISAT) in India, Whitbread and his team are on a mission to extend that kind of information to millions of smallholder farmers.

“My uncle in particular would get quite irate when the rains would come during harvest,” he said. “To yield any kind of profit farming, getting the right climate information at the right time to make lower risk and profitable decisions is really key.

“The farmers we’re working with have advisories from extension agencies but they are not always connected with weather and climate information. We’re trying to change that,” he added.

What to grow and when, through digital extension

The research team started work in the semi-arid farm lands of Andhra Pradesh, where groundnut is the biggest crop, and agriculture relies on rain. Farmers in this state near Ananthapur, lose their harvest, on average, a third of the time.

No surprise, then, that 80 percent of farmers ranked climate variability as their number one constraint to making a profit. The risks of farming look set to become worse, with climate projections for the region indicating higher average temperatures and more frequent extreme events.

“There are a lot of ICT solutions sending agricultural information,” explained Whitbread. “But most often, that information is still very broad, and does not reflect specific farm conditions.

“The best way to help farmers deal with unpredictable weather is to give them the highest resolution information possible in close to real time, so they can make decisions relevant in their own farm context.”

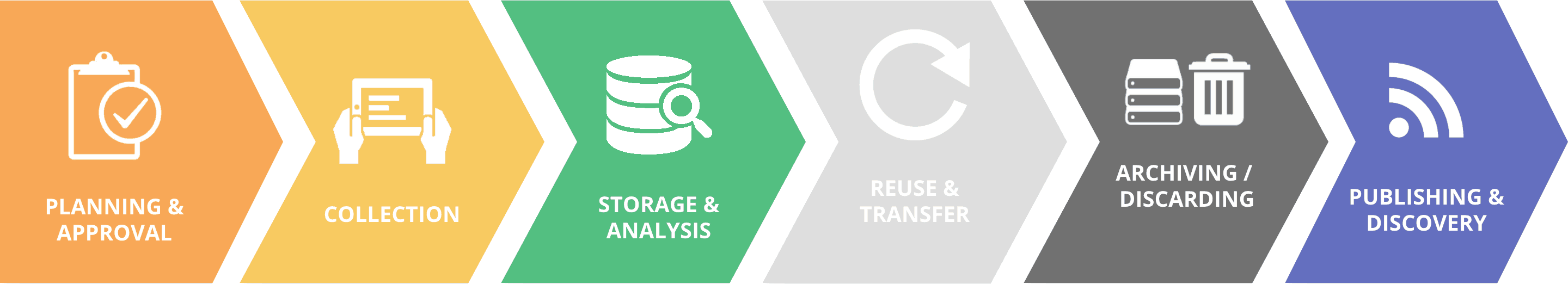

That information comes in the form of the Intelligent Agricultural Systems Advisory Tool, or ISAT. Through a deep understanding of management decisions available to farmers at particular times of the season, and state-of-the-art climate forecasts, the tool presents options for farmers.

Complex weather information is distilled into climate-informed advisories, and presented in the form of decision trees, derived from the analysis of decades of weather science.

Getting science to farmers

“For the first time in India, we’re bringing together weather providers and scientists, to get relevant information to farmers at specific times of year. That means asking meteorologists the kinds of questions farmers would like to have answered, and then relaying that information back to the farm.”

Working with the Indian Meteorological Department, Acharya NG Ranga Agricultural University and Microsoft India, the iSAT tool delivers real-time data, crunched and analysed by researchers, guiding farmers from pre-season planning to in-season management.

During the 2017 monsoon, ISAT was piloted with 417 farmers across four different locations. Mid and end season surveys revealed that more than 80 percent of farmers were satisfied with the frequency, relevance, and understandability of the messages delivered.

More than half rated the messages reliable and correct most of the time, helping them manage risk on their farm. The app also gives information for other important crops too, like sorghum, maize, cotton, and pigeonpea.

“There is sound science incorporated into the decision tree,” said Whitbread. And, thanks to a network of weather stations and rain gauge readings by farmers in pilot villages, rainfall predictions are updated every seven days. Private companies have also provided data.

“But collecting data remains a challenge,” he noted. “What we’re trying to figure out now, is what the lowest resolution of information needed is, to still help farmers make key decisions, but at scale.”

Already, 5,000 farmers in 10 districts of India have been receiving messages directly since 2016. Indirectly, the information reaches another 40,000 farmers, resulting in an estimated 20 percent increase in groundnut and chickpea yield, contributing US$225 a hectare to incomes.

Investment outlook

In the future, the plan is also to get direct feedback from farmers. At the moment, message delivery via SMS is the most realistic option. But two-way communication in the future is critical, to increase message relevance.

At the moment, ICRISAT and partners are keeping the app free for farmers.

“The strength of the CGIAR and scientific community here has been to bring together the agri-tech sector, farmers and the researchers using ICRISAT’s digital agriculture innovation platform, the ihub.”

A pilot is being tested in two districts in Eastern Kenya and will be developed for Senegal during the next wet season. The aim is eventually to drive the scaling out and further innovate through the private sector.

“The private sector have not been very excited by the knowledge intensive requirements of tailoring climate informed advisories,” said Whitbread. But with the success of ISAT, and the enthusiasm of farmers to receive these advisories, we hope to change that in future.

Photo credits: ICRISAT

April 6, 2020

Georgina Smith

Contributing writer

Nairobi Kenya

Latest news