How digital dynamism can transform post-COVID food systems

Big data experts ‘fall in love with the problem’ by exploring new technologies.

“This momentum that farmers have built by themselves is an indication of a larger change in the offing, a systemic shift that we’re probably going to see once COVID is behind us.”

These are the words of Ram Dhulipala of the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics (ICRISAT), speaking at Digital Dynamism for Adaptive Food Systems, a free online conference hosted by the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture.

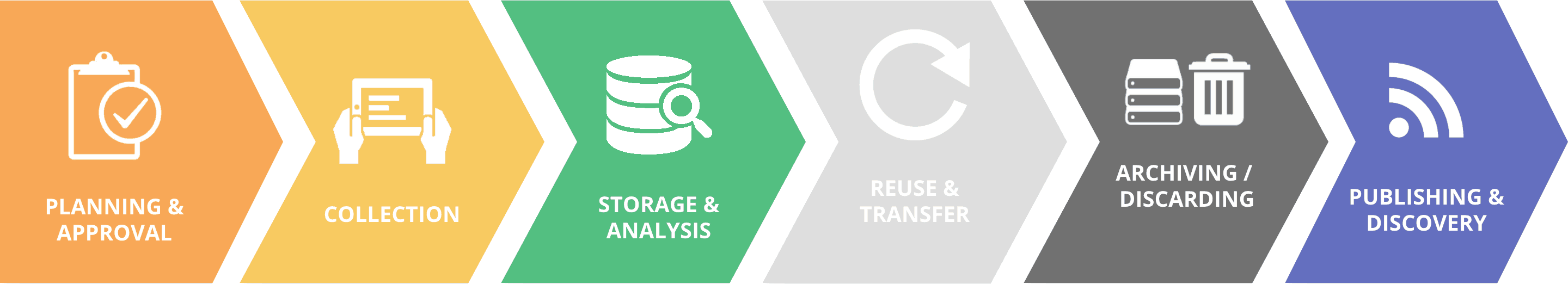

Dhulipala was describing Indian farmers’ response to the difficulties of selling their produce at traditional markets that had “basically collapsed” during lockdown. “Farmers were using simple digital tools like Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp,” Dhulipala explained, “aggregating the produce amongst themselves and finding potential buyers.”

Modern farming is a far cry from the popular image of a sunburnt peasant bent over their spade – it’s now a high-tech business where decisions are informed by satellites, drones and big data.

Take, for example, the work of Accion Venture Lab, a venture capital firm that backs startups using new technologies to help small business, including smallholder farmers and their suppliers, who are otherwise ignored by finance corporations.

“In East Africa, Pula and Apollo Agriculture are using satellite data and mobile payments to finally provide credit and insurance to low-income smallholder farmers,” says Vikas Raj, Accion Venture Lab’s managing director. “They’re really good examples of utilizing digital tools to serve consumers who have historically been considered too expensive to serve.”

And the opportunities for a digitally dynamic agricultural sector are enormous – especially when considering the short- and long-term impacts of COVID-19.

According to Kyriacos Koupparis, head of Frontier Innovations at the World Food Programme, the economic shock of COVID-19 has “dramatically increased” the number of people needing humanitarian support. “For example, in South Sudan, we are now serving an additional 1.6 million people that live in urban areas, in addition to the 5 million people that we were serving before COVID.”

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the U.N. (FAO), is also using innovations in big data to respond to the rapidly changing circumstances in the 130 countries where it works. By mining text from online newspapers and social media, FAO’s Data Lab is using artificial intelligence to track COVID-19 in real time. “We are combining this with data on food insecurity so that we can identify new food insecurity hotspots and better understand the potential impacts of COVID-19,” said Máximo Torero Cullen, chief economist at FAO.

“In humanitarian contexts, innovation is sometimes considered as a ‘nice to have’, but it’s actually imperative,” Koupparis said. “It was imperative before and it is absolutely imperative today as the challenges have multiplied and as our resources are stretched even further.”

“COVID is going to accelerate innovation,” said Marieke de Ruyter de Wildt, founder of The New Fork. “Digitalization and innovation need to hurry up if we want to meet the challenge of feeding everybody and dealing with climate change – that is the elephant in the room.”

The New Fork is an Amsterdam-based tech company that uses blockchain to foster accountability and integrity in agrifood supply chains. Blockchain technology provides a public, decentralized and digital ledger that offers complete security and transparency for all kinds of transactions, including the lifecycle of our food. For example, when there’s a QR code on a bag of coffee at the supermarket that lets a shopper trace the beans back to the farm where they were grown – that’s in thanks to blockchain.

“Blockchain is part of the next Industrial Revolution,” said de Wildt. “We need a more decentralized world to create a more robust world because we will never get ‘post-COVID’. We will have a next COVID, and another, and another.”

Technology is also being tailored to the needs of policymakers, to provide them the information they need to effectively manage their food systems. Earlier this year, Jessica Fanzo, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor at Johns Hopkins University, along with an international team of academics, policymakers and software engineers created the Food Systems Dashboard, which illustrates the interplay between 170 different food systems indicators, running the supply chain from food production inputs to diet and nutrition outcomes.

This is a tool for policymakers to use to dig deep for answers to questions such as why 40 percent of Northern European school-going adolescents don’t eat even one of the recommended five daily portions of vegetables.

Ultimately, the food on our plates (or not, in the case of said schoolkids) comes down to the people getting their hands dirty: farmers.

“There’s deep worry that a lot of people don’t want to be farmers anymore,” said Fanzo. “Younger people are leaving rural places, and the world’s farmers are getting older. It begs the question: who’s going to feed us?”

Andrew Knepp, head of environmental strategy at Bayer Crop Science, sees this as an opportunity for technology to not only make agriculture and supply chains more efficient, but also to attract younger people to the vocation.

“Agriculture is still regarded as a noble profession,” Knepp said. “There’s a tremendous amount of pride in saying, ‘I can produce food, and I can do it in a way that’s more environmentally sustainable.’

“But we’ve got to make sure that solutions are absolutely fair and equitable to farmers. If we’re expecting ecosystem services that are benefiting us as a society, we absolutely need to make sure that farmers are being compensated for the work that they’ve done.”

Ram Dhulipala smiled from the other side of his webcam as he told his favourite quote from tech entrepreneur Uri Levine: “Fall in love with the problem, not the solution.”

“I see a lot of technocrats who want to be agri-preneurs and use their expertise in digital technologies to come up with innovations for agriculture,” Dhulipala explained. “Unfortunately, quite a few of them fall in love with the solution. In agriculture you need to spend a lot of time understanding the problem at a very basic level – only then can you build a solution. You need to fall in love with the problem.”

Feature photo: A relief worker distributes food in Bangkok in April 2020. Ploy Phutpheng, UN Women

October 15, 2020

David Charles

CIFOR

Latest news

I would like to know more about this: Farmers were using simple digital tools like Facebook, Twitter or WhatsApp,” Dhulipala explained, “aggregating the produce amongst themselves and finding potential buyers.” How does this expand upon and/or replace the traditional role of farmer organizations? Aggregation helps both practically, in terms of amassing product in quantities for market, and in terms of empowerment, allowing small and even very small operators to exert clout together, get a fair deal etc. Are both these aspects being looked at? Is there spontaneous empowerment?