Investing in better bang for the extension buck

In Tanzania, overstretched extension services co-designed a tool that gives farmers 24-hour access to pre-recorded agricultural advice to facilitate extension work.

This blog is an effort of the Data-Driven Agronomy Community of Practice to highlight CGIAR’s digital extension work.

In the Newala district of Tanzania, groundnut legumes dot the green landscape. The crops are a lifeline for local farmers. But, as one of the poorest areas in the country, growers hit recurrent problems every year.

From when to prepare land to where to buy seeds, extension services are flooded with questions about farming during peak seasons. With the onset of climate change, matters are made more confusing, as traditional cultivating calendars are rendered useless.

One day, when talking to a District Agriculture, Irrigation and Cooperatives Officer, digital researcher at the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, Jonathan Steinke, says the magnitude of the problem really hit him.

The manager of a dozen extension agents was tasked with reaching thousands of farmers a season – an impossible mission when combined with few resources. “I realized that most farmers will never see an extension agent through the year,” said Steinke. And that could have disastrous impacts for poor farmers who need timely information.

“The manager was very interested to make the work of the few staff he had more efficient. I realized that whatever we can do to reach more farmers would help. But it was really important that we didn’t bring in something entirely new. So we started looking at what was already working well, and then introduced technology to amplify that.”

Finding the right Ushauri – “advice”

Steinke and his team worked together with farmers, researchers and policy makers to define and tackle bottlenecks. Co-designing the service was an essential part of the methodology, ensuring it was relevant.

“We defined the problems, then we selected the technology to help solve them. We could have sent SMS. We could have designed a web platform. But we heard from farmers that they really liked the radio; that they trusted messages delivered through radio, but for one reason or another, they couldn’t always access shows,” explains Steinke.

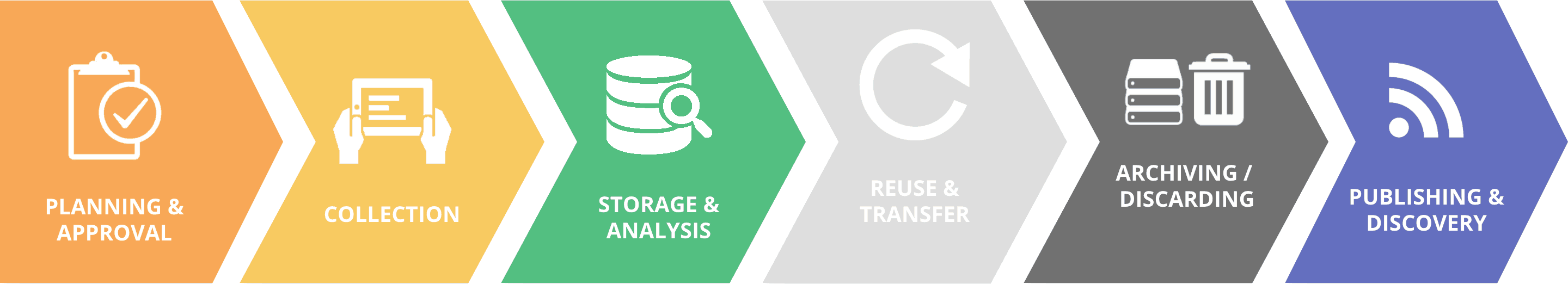

“So, we decided to deliver ‘radio on demand’, providing farmers with relevant agricultural information whenever they want.” Ushauri, meaning ‘advice’ in Swahili, was born. Short radio-like extension messages of two to four minutes are pre-recorded, and accessible for farmers everywhere via regular phone calls.

However, the needs of farmers cannot be fully foreseen. So, the co-designed, 24-hour mobile hotline also allows farmers to record questions. Using an online tool, extension agents record answers, sending messages back to farmers via an automated call.

Making the most of field data

Pilots have already been tested with hundreds of farmers in Kenya and Tanzania, and with key extension workers and decision makers. An important element of the work has been to offer valuable data to strengthen decision-making power. “Decision makers often consider funding extension like a “black hole” – it is invisible work in the field,” Steinke notes.

“Field data tends to stay in the field, and typically, policy makers who fund extension services at the Ministry of Agriculture do not get access it. One of the things we’re doing with Ushauri is to create auditable numbers: What questions are farmers asking, and what problems are they facing in the field? How many messages have been delivered?”

“A lot of communication can be partly automatized, creating higher return on investment for governments. Instead of answering many calls extension agents can save time explaining the same thing over and over again, and farmers can just listen to the audio message without direct interaction.”

Already, useful information has emerged for extension services too. “In Tanzania, we had prepared information about all aspects of groundnut growing, except preparing the ground – preparing rows, distances between rows, how large plots should be,” explains Steinke. “We thought farmers knew that, but then we saw a lot of questions coming up. This information is now included in extension packages.”

What next?

The platform could be used by extension services anywhere, in any language for any context. But Steinke is quick to point out: the platform was developed as a response to needs in Tanzania, and may not fit everywhere. “I don’t think this is a perfect solution for any context, but provided it fits local challenges, we can replicate it,” he says.

Part of the reason the platform has been successful in Kenya, for example, is down to fast network access proliferation. “We asked farmers in Kenya if they could make phone calls in the field. They told us they had 4G! We’re not asking farmers to get out tablets and use satellite data. But mobile network is usually available—even in rural areas.”

The team is now expanding the pilot and exploring funding models. Currently, the platform can be rented by public or private organizations, but the aim is to incentivize governments to fund it, cutting extension costs and improving efficiency.

The aim is also to make digital extension more inclusive. “Often, digitalization favours market logic and richer members of society,” explains Steinke. “We want to bridge the digital divide, and make sure applications do not strengthen disparities that already exist, but bring better opportunities for everyone.”

April 6, 2020

Georgina Smith

Contributing writer

Latest news