The Bots Are Here—and They’re Protecting Our Crops

Armed with AI-equipped smartphones, African farmers should be able to detect and deal with potato viruses before they get out of hand.

The story was originally published by Scientific American.

***

Whether it’s our jobs, our privacy or our democracies, artificial intelligence and smart technology often seem to pose nothing but threats. But one “threat” we should welcome from the effects of machine learning and new technology is the disruption of pests and diseases that attack crops, cause food shortages and contribute to famines worldwide.

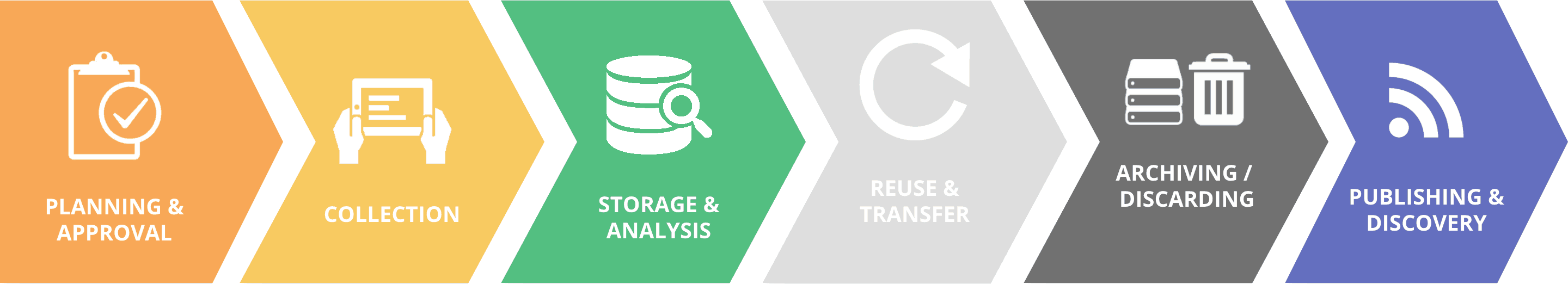

Rapid strides in open-source digitization mean we have the tools to equip farmers with intelligent systems that can identify pests and pathogens, allowing them to take action long before any losses occur.

This revolutionary use of technology arms smallholder farmers, who are increasingly gaining digital know-how, with the means to identify quickly and accurately when their crop is under threat, and how best to combat that threat.

With the agriculture sector estimated to lose around $540 billion worldwide in damage from invasive pests and diseases each year, and with climate change contributing to the rise and spread of new challenges to healthy crops, global food security will depend on the adoption of these new digital tools.

This means making them accessible, affordable and comprehensible to the millions of smallholder farmers responsible for up to 90 percent of food production in developing countries.

With this in mind, I’ve been working with the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and PlantVillage at Penn State University to develop a smartphone application that gives farmers real-time diagnoses of crop disease, using AI algorithms trained with images of diseased crops.

The PlantVillage app, for example, is being trained to detect diseases in sweet potato, which is a hugely important crop in sub-Saharan Africa. Potato blight alone is estimated to cause annual losses of $5 billion, with potato and sweet potato farmers in developing countries losing up to 60 per cent of their yields to pests.

Farmers don’t need much technical knowledge or literacy to use the app; they simply point a phone at the infested crop and the app will provide an accurate diagnosis using the talking AI assistant, Nuru.

Sweet potato feathery mottle virus and sweet potato chlorotic stunt virus, for instance, are the most common viral diseases affecting sweet potato; they can reduce yields by half, and in severe cases by up to 100 percent.

The symptoms of these viruses are often difficult for farmers to discern, which means they regularly go untreated. But through machine learning trained with confirmed symptoms of infection, AI would be able to draw upon its archive of all possible signs to recognize the diseases and help farmers take earlier action to save their crops.

This kind of technology has already shown promising results in tackling crop pests such as fall armyworm, an invasive caterpillar native to the Americas that spread to Africa in 2016 and has now reached Asia, causing huge losses to maize crops.

PlantVillage for example, has been adopted by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and monitors the spread of the voracious caterpillar in around 70 countries. It uses the Nuru talking app along with machine learning and AI to immediately confirm to a farmer whether fall armyworm is damaging their crops. It then provides information on how to stop the pest while providing a real-time view of infestations across maps of Africa for other app subscribers.

Beyond pests and disease, new satellite technologies can also help assess the productivity of crops and water availability to guide farmers in their planting decisions.

Satellites can provide accurate data to suggest where crops might be best placed to optimize production or to prepare more adequately for extreme weather such as droughts and floods.

For a smallholder farmer, this kind of knowledge can be the difference between persevering and prospering in the face of changing conditions that bring new and emerging threats.

To make such innovations widely available to all of the farmers who need them most worldwide, then, we need significant and long-term investment because regardless of the power of the technology, it remains redundant without constant promotion, training, updating, maintenance and expert support of the system.

But while the world is facing unprecedented global challenges, never before have we been so well-equipped to tackle them. The Fourth Industrial Revolution can be the moment the world uses technology as a force for good to tackle global hunger, malnutrition and inequality.

September 2, 2019

Jan Krueze

Scientific American

Latest news