A streamlined tool for rural household surveys – Q&A with Jim Hammond on RHoMIS – the Rural Household Multi-Indicator Survey

Interview by Vanessa Meadu.

There are great opportunities to improve the process of gathering information from farming households, particularly in low and middle-income countries where development projects depend on solid data for their success, and existing data resources are scarce.

Enter RHoMIS – the Rural Household Multi-Indicator Survey, which aims to reduce the costs, time requirements and reporting burdens for those who carry out household surveys. The development team have built and used a bank of survey questions based on internationally recognised indicators, covering all aspects of farming systems, including livestock. The database contains a wealth of information that may unlock important solutions to livestock challenges.

We spoke with Jim Hammond, a scientist based at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), who co-leads the RHoMIS team, about how RHoMIS could help close livestock data gaps and uncover new insights.

Vanessa Meadu: How can RHoMIS help improve the reliability of data on livestock and rural livelihoods in Low and Middle-Income Countries?

Jim Hammond, ILRI

Jim Hammond: RHoMIS has been used to interview over 25,000 farmers in the past five years. We have gathered a huge amount of data on livestock and rural livelihoods and have made a real effort to ensure there is a high level of reliability in the data quality. Compared to the RHoMIS approach, typical household surveys are organised very differently, meaning the data captured is difficult to compare. It’s a challenge to make sense of such data and to bring different studies together. RHoMIS allows for a harmonised approach. The tool improves comparability between locations, by asking the same questions in lots of different places. We reduce the survey burden on the farmers by asking for a degree of precision which the farmers are comfortable with.

In each project that we work on, we verify the validity of the data that’s coming in, for example correlating various independent indicators on household food insecurity scores. We also compare the credibility of the overall data with the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study – Integrated Surveys on Agriculture (LSMS-ISA) and the ImpactLite survey data. A recent analysis showed that the credibility of data from RHoMIS was at least as good and in some cases better than ImpactLite or LSMS-ISA.

By using the same modules of questions again and again we can look for biases that shape how farmers answer questions, and hone the

questions to be more effective. For example, we are currently conducting a study which compares the various recall periods used against monthly 24-hour recall data, in order to establish the best way of asking certain questions.

Ultimately, by making these household surveys more efficient, robust, and comparable, we aim to free up more time and budget for other project activities, and develop a bank of data available to the wider community.

VM: What advantages can RHoMIS bring for measuring and analysing animal health and productivity?

JH: The RHoMIS approach is about minimal effort, maximum information. The advantage of RHoMIS is the established and proven library of questions that can quickly capture the most useful level of detail. We have intentionally designed the questions to be asked at a household and whole farm level, rather than fields or plots. And we ask about whole herds, not individual livestock. For example, we might ask “per animal species, what diseases have been present in the last year and what measures were taken to treat those diseases?” or “from all your animals for the wet season, how much milk did you harvest per day”. We need a level of detail that is easy for farmers to recall. We have found that if more detailed questions are asked, for example about each animal’s milk output, there is a higher risk of multiplication errors when scaling up the data, and thus undermining the research effort.

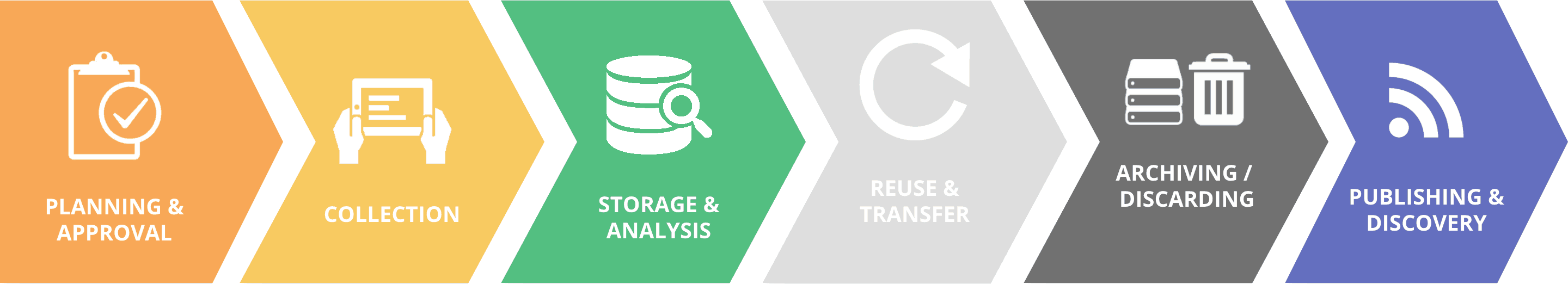

VM: How do you find the right balance between standardization and flexibility when designing questions?

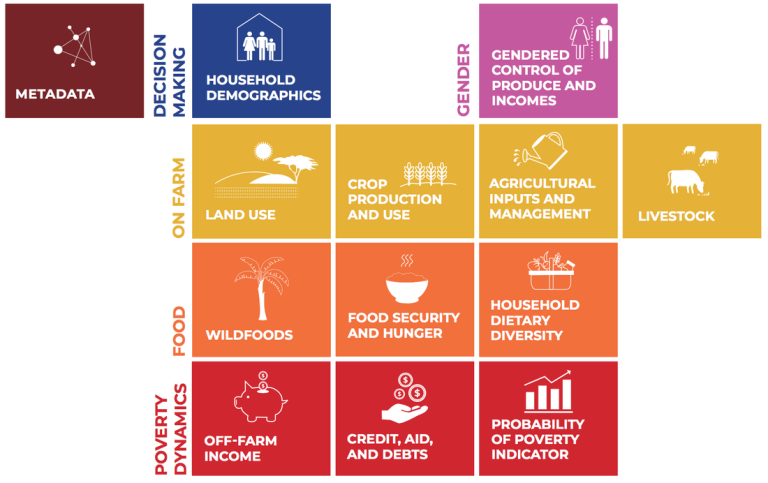

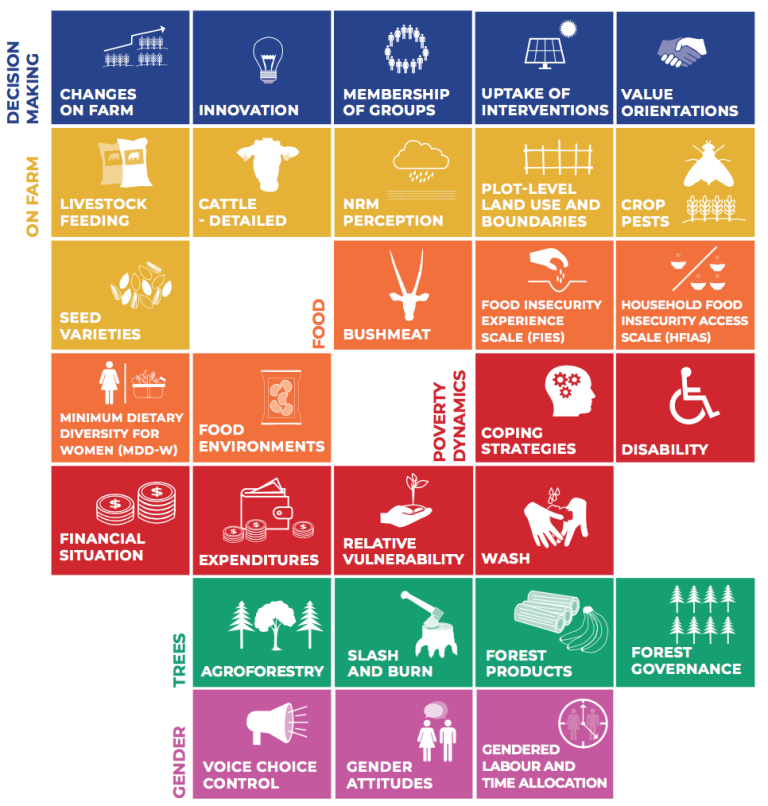

JH: We started from the standpoint: “What are the questions that every rural agricultural development project needs to ask?” If we want to develop data that is comparable between locations, there needs to be a degree of standardization. At the same time, it is essential that RHoMIS is flexible enough to be used in lots of different projects and able to incorporate unique needs and adapt the questions to a particular context. To strike the balance between standardization and flexibility, we have developed a core RHoMIS survey that covers the whole farm system, which can be tailored with extra questions for a specific project, for example with a focus on animal feeding. Having now worked with over 50 projects in 30 countries, certain topics come up again and again, allowing us to fine tune the questions on that topic until they can be considered a coherent “module.” For example, amongst our library of modules, we have one on animal feeding that can be used for future projects.

RHoMIS survey core modules

RHoMIS survey additional modules

VM: What kind of insights can RHoMIS data generate that would not otherwise be possible?

JH: Because the RHoMIS tool takes a farming systems perspective, including livelihoods, food security, and interactions with the built and natural environment, we gain a consistent level of detail over a wide range of topics. This allows us to look for system interactions that are observable in a widespread diversity of locations, projects, cultures, or climate zones. The data can shed light on previously unknown interactions that should be acknowledged in the high-level design of development programs.

A recent study using RHoMIS data revealed that, as particular farming products become more commercialized and generate more income, the control over income shifts from women to men. We saw that pattern quite widely in the data for four different east African countries. We can disaggregate it by crop or livestock products, and see that the gendered impact of commercialization of crops was higher than livestock. The main implication is for household nutrition: there is evidence that when female household members have more control over food stuffs they are more likely to reinvest into the household and foods for the children. It shows there are trade-offs between commercializing agriculture to help households become wealthier, versus households remaining nutritionally secure when they don’t commercialise.

Because we’ve got indicators covering so many parts of the farming system, we can assess these particular trade-offs. And because we have these indicators in lots of different locations and projects we can bring the data to test different hypotheses.

VM: What are the limitations of RHoMIS?

JH: As with any research tool, there are inherent limits. We try to keep surveys under 60 minutes (and absolutely under 90), and have to collect the most information we can in this time. This means it’s often not possible to delve deep into any particular topic. But the purpose of the tool, part of its unique value, is to give an overall characterization of a farming situation, and identify hotspots for future work.

Another challenge we find is when we receive data from lots of different projects. Each one may have a different sampling strategy, and may have engaged with a limited set of farmers, for example an exclusive focus on cattle farmers. This introduces biases into the overall database. We need to use very good metadata to ensure users understand what each project represents.

VM: Who else would you like to see using the survey and data?

JH: In addition to our own analyses and publications, it is our dream that the database is used by the global research community, and by the donor community. If governmental statistics bureaus take up the survey tool, the amount of data collected would really mushroom. For example, the tool could be further adapted to gather information and track dynamics between major agricultural census exercises and provide rapid snapshots of the situation. Additionally, we would like to further promote the use of RHoMIS by NGOs. We have already seen how it can help international NGOs conduct baseline and endline surveys and how it is able to generate unique insights abut a project’s impact.

VM: Is the RHoMIS data currently openly available?

JH: For now, it’s a research tool. A big step will be making the data open source and publicly accessible. We expect the first tranche of data to be released later in 2019, with annual updates to the database. The use of that data will probably be an important catalyst for making a step-change in the way the whole of RHoMIS is used.

At the moment to build the questionnaires, or to interrogate the database, you need scientific skills or to run your work through our team. There is an ambition to move from where we are, a well-tested research tool and growing database, towards a more accessible open-source package that can be downloaded from the internet and used independently. A community of practice has developed around the tool, made up of groups who analyse the data, and we had our first visioning meeting earlier this year.

I’d like to encourage LD4D community members to use the survey tool and the data when it comes out later this year. There are a number of publications coming out based on the data that could be of interest to anyone working in livestock development.

More information:

Visit the RHoMIS website for more information, publications, data and analysis.

Read more:

Steinke et al. 2019. Prioritizing options for multi-objective agricultural development through the Positive Deviance approach.

Steinke et al. 2019. Household-specific targeting of agricultural advice via mobile phones: Feasibility of a minimum data approach for smallholder context.

Bosire et al. 2019. Adaptation opportunities for smallholder dairy farmers facing resource scarcity: Integrated livestock, water and land management.

Jim Hammond is a post-doctoral scientist at the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Vanessa Meadu is Communications and Knowledge Exchange Specialist for SEBI – Supporting Evidence Based Interventions, based at the University of Edinburgh’s Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies. SEBI acts as secretariat for the Livestock Data for Decisions (LD4D) Community of Practice.

Lead photo credit: S. Chesterman (ILRI)

July 17, 2019

Vanessa Sebi