Stand out from the herd: get to know the data behind your livestock facts

It pays to know the age, accuracy and scope of your livestock facts say the authors of a new publication that explores the data behind popular livestock figures

by Vanessa Meadu and Gareth Salmon

The role of livestock in supporting human well-being is increasingly contentious. News outlets carry divisive messages about the environmental, economic and social aspects of livestock and animal-based products. Critics and advocates toss around ‘facts’ and ‘evidence’ to make their claims, but these facts are often divorced from their data sources and may be intended for a different purpose. In a new paper investigating the origins of popular livestock facts, the authors call upon advocates and researchers to recognise the context, accuracy and age of the evidence they use in discussions the future of livestock.

Reconnecting the facts to their origins

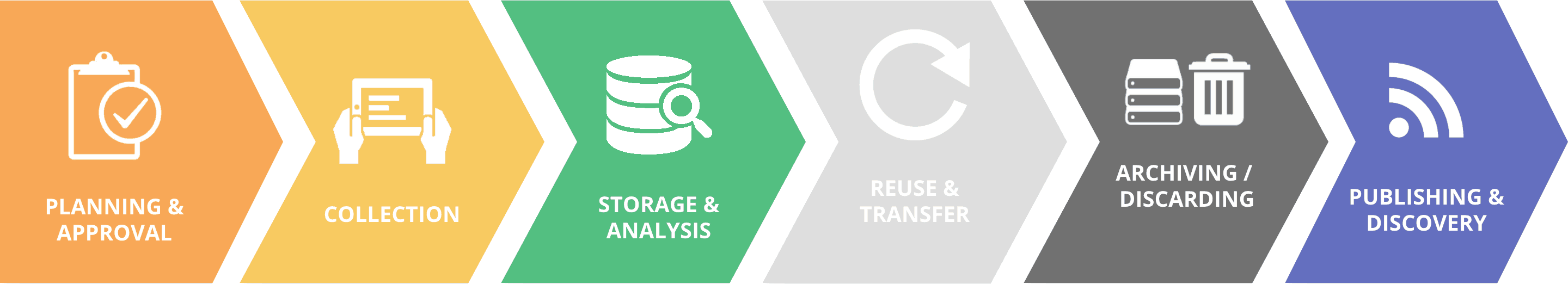

The Livestock Fact Check project aims to help inform discussions about livestock production through a balanced examination of some commonly referenced livestock ‘facts’. The project’s key findings are useful to anyone engaged in discussions about livestock and society.

According to the authors, livestock ‘facts’ are frequently communicated without an understanding of their origins. Facts are often cited in ways that suggest more certainty than the data supports. They may be used by journalists who want to summarise complex issues, by politicians looking to justify a decision, or by individuals promoting a particular position.

The researchers investigated the data and evidence behind eight commonly used livestock facts, and in doing so, discovered some interesting interpretations and sometimes out-of-context uses.

Example fact check: Do livestock really support the livelihoods of one billion poor people?

Most publications citing this number aim to demonstrate the importance of livestock to humanity and especially as a focus sector for development efforts. The researchers discovered that many sources did not cite a specific reference, and when they did, it was not the primary source of research. In fact, the number traces back to a 1999 study funded by the UK Department for International Development, led by Livestock in Development (LID), calculated the global number of poor livestock keepers as 987 million. This figure is based on publications and statistics that are now more than 20 years old. Since 1999, the global population has grown by over 1 billion people (mostly in low and middle-income countries), and the global definition of ‘poor’ has changed. A more recent calculation of the number of poor people who depend on livestock has not been done. Does this matter, ask the authors? On the one hand, they note that this approximate ‘large number’ may be good enough to highlight the importance of livestock to future food security efforts. On the other hand, more accuracy would be needed in order to inform specific investment activities, to understand trends and monitor impact.

- Download the original brief: Livestock and livelihoods: Do livestock support the livelihoods of around one billion poor people globally?

The use and abuse of livestock models

If you want to make use of livestock facts to inform your arguments, it helps to understand how livestock systems models work to make sense of complex systems. There are a multitude of models which use different methodologies, rely on different sets of assumptions, and work within a defined scope. Models operate by processing data: the quality, availability and resolution of livestock data all determine how well the modelled results illustrate or predict reality. The authors note that when different models are used to investigate the same production system, they may produce widely varying results. For example, estimates of the livestock sector’s contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions has varied from 8 to 51%, depending on which modelling approach is used.

Another risk relates to comparing ‘facts’ derived from different models. To responsibly do this, the authors recommend you try to understand the model’s methodologies, scope and assumptions. They note that solutions such as the Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model (GLEAM) of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation can help overcome this problem, as it encourages consistency and allow informed comparisons of different scenarios.

Be clear about uncertainty and variability

It is challenging to communicate livestock information when global livestock production systems are brimming with uncertainties and variability. It may be tempting to brush aside uncertainty and variability in order to make a clear point, but the authors warn that this is unproductive and can even be misleading. For example, when communicating ‘facts’ about livestock’s contribution to climate change, you need to be transparent that these ‘facts’ largely come from modelling exercises with considerable recognised uncertainty. Similarly, it is important to acknowledge the variability in greenhouse gas emissions from different production systems, as this indicates opportunities for more sustainable approaches to livestock production.

A community initiative to support better-informed discussions

To date, eight facts have been investigated and launched in a way that stimulates discussion on these issues. All factsheets are reviewed by members of the LD4D community. The project will remain open to investigate future livestock evidence, with this journal publication offering a peer reviewed presentation of progress to date.

Further reading

Journal article:

Livestock Fact check project:

Vanessa Meadu is Communications and Knowledge Exchange Specialist with Supporting Evidence Based Interventions (SEBI), based at the University of Edinburgh’s Royal (Dick) School of Veterinary Studies. Gareth Salmon is a Researcher with SEBI. SEBI facilitates the Livestock Data for Decisions (LD4D) Community of Practice.

January 9, 2020

LivestockData.org News