Designing mobile phone solutions for agricultural extension: Perspectives matter!

Creating successful digital tools for agricultural advisory requires designers to step into farmers’ shoes. And extension agents’ shoes. And their supervisors’ shoes…

Too often, gaps between digital design and the users’ reality arise because researchers make assumptions about their target audience. To avoid failure, participatory design methodologies can help to place the users at the heart of the digital development process. User-centered design, or design thinking, is a framework that helps to understand information needs, select suitable technologies, and adapt them with feedback from prospective users.

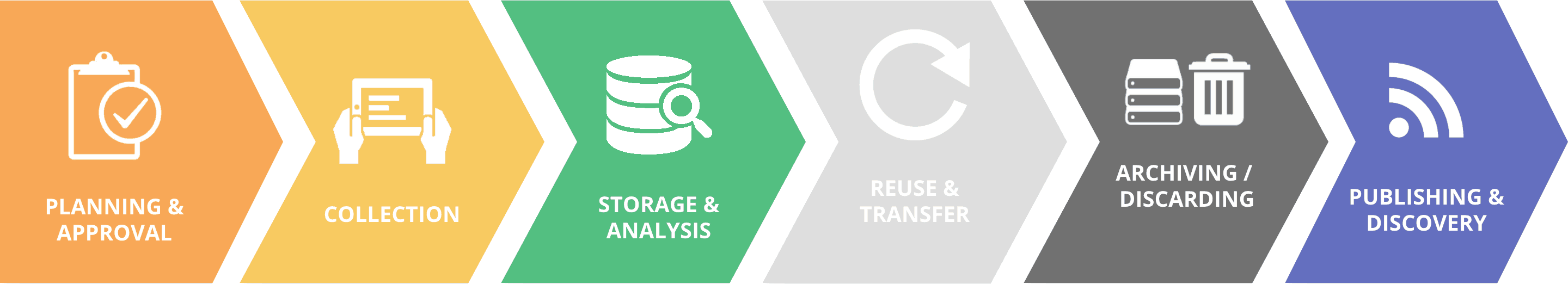

In user-centered design, future users (farmers, extension agents, or researchers) participate in specifying the problem, selecting partial solutions, and refining a new digital tool or service through iterative trials. Design thinking is already part of a good practice widely promoted by the international community, for instance through the Principles for Digital Development.

User-centered design for digital advisory services

There are obviously many factors hindering the success of digital agro-advisory services. For example, what types of information do farmers really need to make decisions? How do they typically use their phones? Which information sources do they trust? The answers to these questions, as well as others, are often based on the developers’ assumptions about the design inquiries.

Another often overlooked problem consists of focusing the design on information dissemination to farmers only. Agricultural extension occurs within a complex network of information flows. Seeing farmers only as recipients and extension agents only as originators of information will often over-simplify reality – leading to inadequately designed mobile services.

Therefore, our recent development of a digital agro-advisory service in Tanzania, called ‘Ushauri’, started by asking: What are the information needs and communication preferences of farmers, and of extension agents, and of their supervisors? We believe that to be sustainable, a digital advisory service should do more than just deliver information to farmers. Adoption by farmers alone is unlikely to be enough. After all, someone needs to make sure the information is ‘sent’ in the right way. And this somebody – usually an extension agent – needs a sustained incentive to use the tool.

A digital service that addresses the information and communication needs of all key stakeholders in agricultural extension has the potential to get mainstream, rather than abandoned.

Generating added value for all extension stakeholders

We spoke to farmers, extension agents, and senior decision-makers of the extension system in Tanzania. Our research revealed key information and communication shortcomings for each group. Understanding the different perspectives on the same situation helped us to shape a service that addressed the different needs simultaneously.

Communication between farmers and agents suffered from the high number of farmers each agent had to attend. On the bright side, many farmers had already talked to their agents over the phone when we started our research. On the downside, farmers often had urgent questions but were not able to quickly reach an extension agent. Farmers expressed the need for rapid answers and extension agents needed a system to manage the great number of farmer phone calls.

At the same time, extension supervisors and policy-makers wondered how to evaluate the performance of their staff. Although extension agents document their activities in field books, this information cannot be analyzed at larger scales. Decision-makers expressed the need for better insights into agricultural advisory on the ground: How many farmers are we serving? How many of them are women? Which value chains require the most support?

Ushauri: serving diverse users with diverse knowledge needs

Our insights on the information needs of the different extension stakeholders led us to the concrete design idea behind ‘Ushauri’ (described in detail in this article). In a nutshell: farmers call Ushauri and access an automated, IVR-based hotline, where they can listen to pre-recorded answers on the ‘frequently asked questions’ option. Farmers can also record further questions. Much like incoming emails, these questions then appear on an online dashboard that extension agents access through their smartphones. The agents can record and send an answer back to the farmer as a push-call. Over time, each agent will be able to build up a library of voice messages that can be sent back to farmers, allowing them to rapidly respond to any and all repeated questions. Our pilot programs in Tanzania and Kenya showed that agents were able to serve more farmers in less time using Ushauri. Farmers needed to wait less time for getting advice on their specific farming problem.

In addition, farmers are registered with demographic data, including gender and location. This allows Ushauri to generate insights for decision-makers about the provision of agricultural advisory: who is asking what, where, and when. This information can be used for more targeted planning of interventions and expenditures in agricultural extension.

In the development of Ushauri, user-centered design methods helped to understand the limitations of the current extension service and the diverse needs of its stakeholders. The method allowed the team to develop a solution fit for the target context and has been positively reviewed by all user types in our pilots. In Kenya, Ushauri will soon be used by a livestock cooperative. In an alternative setting, a user-centered design process may have led us to design something completely different. The first lesson on our journey, however, was the importance of framing who we mean by ‘user’. We needed to learn that for a digital advisory service to be accepted, it must serve not only farmers but the extension system as a whole.

Further reading:

Ortiz-Crespo et al. (2020) User-centred design of a digital advisory service: enhancing public agricultural extensions for sustainable intensification in Tanzania. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14735903.2020.1720474

Steinke et al. (2020) Tapping the full potential of the digital revolution for agricultural extension: an emerging innovation agenda. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14735903.2020.1738754

April 22, 2021

Jonathan Steinke, Berta Ortiz-Crespo and Anna Müller

4 - 4Shares

Latest news

4 - 4Shares