Digital warning system and coupling with crop model to boost wheat farmers’ resilience in Bangladesh and Brazil

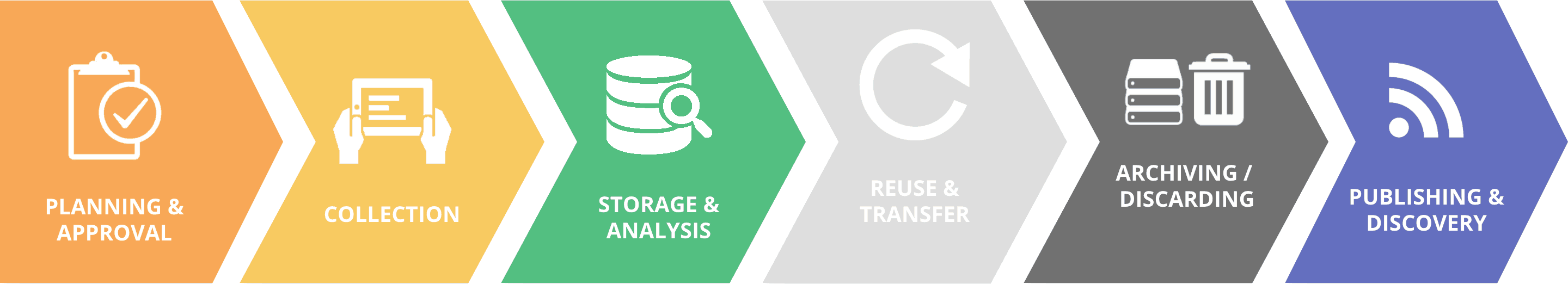

A new digital early warning system for wheat blast disease integrates mathematical models that, when combined with weather forecasts, can simulate disease growth and risks to forewarn against potential outbreaks.

Outbreaks of wheat blast in South Asia – a region where people consume over 100 million tons of wheat each year – have an enhanced impact on food stability and income security. In 2016, wheat blast struck South Asia unexpectedly, with crop losses in Bangladesh averaging 25 to 30 percent, threatening progress in the region’s food security efforts. Estimates are that blast could reduce wheat production by up to 85 million tons in Bangladesh, equivalent to $13 million in foregone farmers’ profits each year when outbreak occurs.

That’s why there’s optimism from farmers and scientists alike about a new digital early warning system that integrates mathematical models that, when combined with weather forecasts, can simulate disease growth and risks to forewarn against potential wheat blast outbreaks. With three years of data recorded, the system, which was originally piloted in Brazil where wheat blast has been a concern for several decades, is now being rolled out across Bangladesh to deliver real-time disease updates to extension workers and smallholder farmers via SMS and voice message.

“Through collaborative research we have established a model to identify areas at risk of wheat blast infection with five days advanced warning,” said Timothy J. Krupnik, senior scientist and systems agronomist at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT). “It can provide Bangladesh’s 1.2 million wheat farmers a head start against this disease.”

This data-driven early warning system analyzes environmental conditions for potential disease development in crucial wheat growing areas of Bangladesh and Brazil. Through this information, the system generates forecast maps and automatic advice for farmers of where and when infection is most likely to strike.

“The model was originally developed in Brazil, but we have worked closely with collaborators from Brazil and the Bangladesh Meteorological Department (BMD) and Department of Agricultural Extension to develop a warning system positioned for use by extension workers and farmers,” Krupnik said.

Currently, farmers are advised to apply fungicides on a calendar-based preventative basis. This is costly and can have negative environmental effects. Instead, the early warning system pushes advice to extension agents and farmers, indicating when disease control is really needed.

“Our hope is that it will help reduce unnecessary fungicide use while assuring that farmers can implement cost-effective and resilient practices to overcome wheat blast risks,” Krupnik said.

The importance of collaboration

With limited information on wheat blast, Krupnik initiated a collaboration with agricultural researchers in Brazil – where the disease originated in 1985. Professor Jose Mauricio Fernandes, a crop pathologist from Embrapa, and Mr. Felipe de Vargas, a computer scientist, with Universidade de Passo Fundo, were familiar with wheat blast and had already developed an initial mathematical model of disease development. The team collaborated to transfer the model to South Asia and build it into a more comprehensive and location-explicit early warning system that has now been endorsed by Bangladesh’s Meteorological Department, Department of Agricultural Extension, and the Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute. Thousands of extension agents will begin receiving disease early warnings based on model outputs and analyses starting in early 2020 across wheat growing areas throughout the country.

The team plans to adapt the system to help manage other pests. They are also working to improve predictability of when wheat may reach most susceptible stages for crop infection based on crop phenological model runs to pin-point the timing in addition to location of outbreak risks. In a first-of-its-kind effort for this disease, the team has successfully coupled the Decision Support System for Agrotechnology Transfer (DSSAT) model with the disease epidemiology model, allowing estimates of potential yield losses due to wheat blast. The applications for this work to improve early warning and forecasting systems are just beginning to unfold.

“We improved preliminary modelling framework to manage data requirements to predict the time and location of blast outbreaks in Bangladesh, Brazil, and beyond,” Fernandes said. “I am excited to see how it increases farmers’ resilience to disease risks in Bangladesh.”

These efforts were supported by the USAID funded Climate Services for Resilient Development Project (CSRD) in South Asia, the USAID/Feed the Future and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation supported Cereal Systems Initiative for South Asia (CSISA), and by the Crop Modeling Community of Practice from the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture.

January 16, 2020

Matthew O’Leary

International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

11 - 11Shares

Latest news

11 - 11Shares

Hi Edwin,

If you can send an email to bigdata[at]cgiar.org we can send you the pdf detailing this information.

Regards,

The BIG DATA team.

I wonder where is the mathematical model?

Hello, Edwin. We are in touch with the webinar presenters to locate information on the mathematical models and will keep you updated. Thanks!