Leveraging digital tools to transform Africa’s food systems

As Covid-19 continues to disrupt food distribution systems, it is not only critical to ensure that supply chains continue to function, but also to assess how to emerge stronger from the crisis.

John Agboola is a farmer and an agricultural specialist who is passionate about agricultural research for sustainable development in Africa. He is a value chain catalyst, agricultural mechanization and communication expert with a degree in Agricultural Economics and Extension.

He has served as the communication focal person for YPARD Nigeria, is an Africa Lead Champion for Change, and joined the first cohort of Youth in Data for the CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture.

***

One of the foremost challenges facing African countries amid global Covid-19 lockdown is how to safeguard access to basic services for their citizens.

Food is the most fundamental human need. As Covid-19 continues to disrupt food distribution systems, it is not only critical to ensure that supply chains continue to function, but also to assess how to emerge stronger from the crisis. This requires examining how food is produced, and distributed across the entire agricultural value chain, and tackling any identified gaps from the farm level to end consumers.

To remain relevant at farm level, extension models must embrace new technologies

At the bottom end of this chain, agricultural extension systems play an important role in improving farm productivity.

While they provide much-needed information and technical support, traditional extension models based on face-to-face contact with farmers are not only expensive to maintain but slow to respond to a rapidly changing market environment. Moreover, their focus on external inputs, such as hybrid seeds and fertilizers, can be costly for smallholder farmers, and, if used incorrectly, become harmful to soils, water, and other natural resources.

In many parts of Africa, formal extension systems are not only poorly under-funded, but they also struggle to remain relevant to farmers’ needs, especially in the face of accelerated land degradation, erratic weather patterns due to a changing climate, and other challenges. A recent report revealed that the average ratio of extension agents to farmers in Africa is 1:2,000. The disparity is significantly higher in Nigeria, where the ratio varies from 1:5,000 to as high as 1:10,000.

Due to the scarcity of extension agents, most farmers do not seek advice before commencing agricultural operations. In an interview, Samuel Sanondo, a maize farmer in Taraba, northern Nigeria, reported that since he started farming more than 10 years ago, extension agents have only visited his farm twice.

Advancing digital extension advisory services

Photo: CTA. An extension agent sharing information with farmers.

A more cost-effective alternative to maintaining large numbers of extension agents is to adopt information and communication technologies (ICTs) to provide more targeted, and timely information to farmers. Unfortunately, Africa continues to lag behind in the development of virtual platforms for sharing the latest data, and good practices on key topics such as crop agronomy, livestock management, pest and disease control, and weather information.

In another interview with five young agribusiness ventures from Nigeria, Ghana and Cameroon, I learned about a range of challenges faced by farmers, from inaccessibility to input, market, extension and support systems faced as a result of the pandemic.

The CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture tagline “Feeding the World Byte by Byte” reaffirms the unique opportunities offered by ICTs, and other technological innovations, to feed a growing planet.

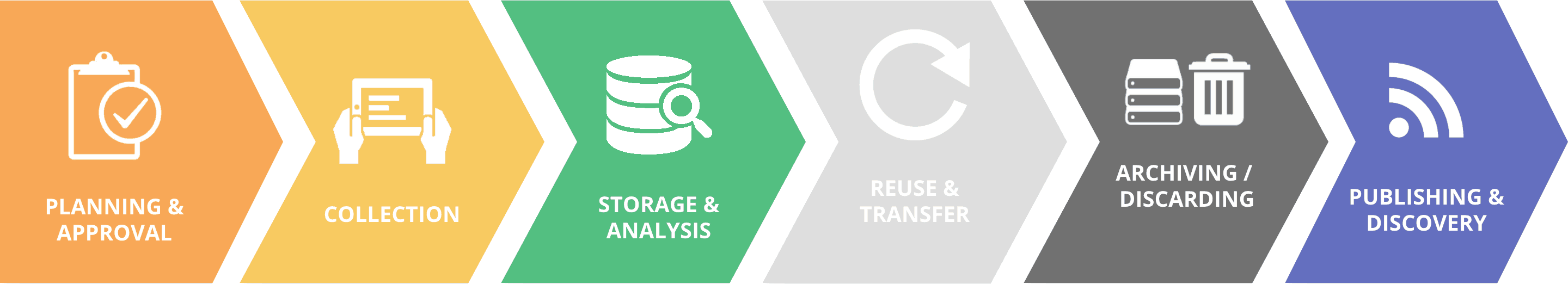

Covid-19 lockdown measures add further urgency to the call by the Malabo Montpellier Panel report to transform African food systems through digitization. One of the nine key areas of digital interventions highlighted in an infographic summarizing the report’s findings focuses on the importance of strengthening skills development and digital literacy for farmers, and other actors in the food systems.

Another key player in agricultural innovations and technology in Africa is the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation ACP-EU (CTA). One of the initiatives supported by the centre is the Ghana Farmerline, which connects farmers to up-to-date weather information, agronomic tips, market prices, and nutritional advice, via SMS.

In Nigeria, Kitovu Technology Company uses GPS coordinates to perform plant health analysis for farmers registered under its platform. The company makes use of remote sensing tools to monitor plant health and manage pests and diseases in a cost-effective way. This also aids in data collection and the provision of information from farm to market.

The current global health crisis presents both challenges and opportunities for farmers. The restrictions on travel, as well as social distancing rules, have highlighted the advantages of leveraging digital tools to keep food production and agricultural knowledge transfer unhindered during this, and future crises.

This article is part of Covid-19 Food/Future, an initiative aiming to provide a unique and direct insight into the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on national and local food systems. Central to our approach are the experiences of young, urban and peri-urban farmers, street vendors and informal retailers, and low-income consumers. Follow @CovidFoodFuture on Twitter. Covid-19 Food/Future is an initiative by TMG. ThinkTank for Sustainability, or on Twitter @TMG_think. Funding for this initiative is provided by BMZ, the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Feature photo: ISS blog.

July 15, 2020

John Agboola

27 - 27Shares

Latest news

27 - 27Shares