Monitoring Crop Harvest using Satellite Remote Sensing

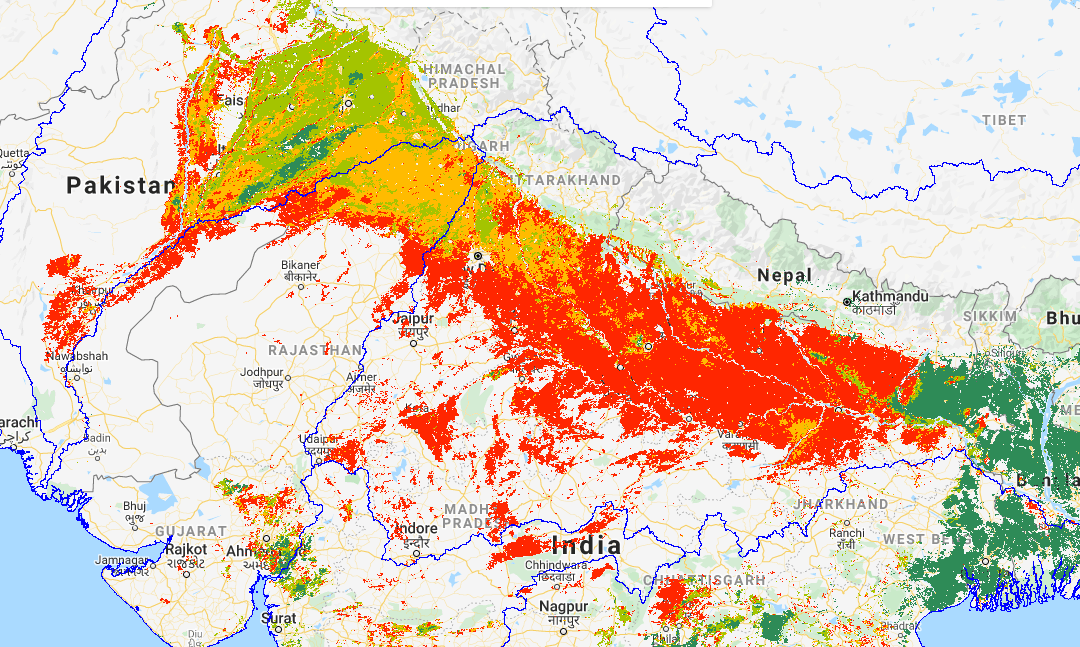

Take a look at the satellite map below. That vast swathe of orange and red across northwestern India and Pakistan depicts crops that have ripened in the last couple of weeks. Meanwhile, the areas of pale and dark green, in Pakistan, Bangladesh and West Bengal (India), represent crops that are still maturing in the fields. This bounty of wheat, fruits and vegetables could feed millions of people for months.

In any normal year, a bumper crop would be cause for celebration. However, with the world in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic, this season’s harvest is posing a dilemma for governments: how to strike a balance between ensuring crops are harvested and taken to market – and restraining citizens’ movements. Major agricultural economies are among countries putting in place social distancing and lockdown measures to try and contain outbreaks before they overwhelm health services. However, this is having a major impact on food production.

In India, where harvesting is under way, the government has issued guidelines for agricultural workers. Six days after it announced a nationwide lockdown, which is currently in place until May 3rd, the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) published extensive guidance to farmers on what they should and should not do. For example, it states that measures of personal hygiene and social distancing are to be followed “by those engaged in harvesting of all field crops, fruits, vegetables, eggs and fishes before, during and after executing the field operation.” And it calls for mechanised harvesting to be followed wherever possible. Meanwhile, state governments are considering staggering and delaying crops arriving at market in order to reduce the throngs selling produce at any one time.

The reality on the ground is more complicated, however. At Lasangaon, in the west Indian state of Maharashtra, lies Asia’s largest onion market. Accounting for a third of India’s onion province, it continued functioning after lockdown was announced, albeit on a shoestring staff, until rumors of a local case of COVID-19 spread, and staff failed to turn up for work. As a result, 450 tonnes of onions sat waiting to be transported across India. Other farmers have also reported workers staying at home out of fear of the virus. And some districts are struggling to get the farm machinery they need for harvesting at the appropriate time to the required locations.

Rice is one of Asia’s main staple foods. In India, exports have already been hampered by the pandemic, and further disruption is likely. The same is the case for another top rice exporter, Vietnam. Greater demand for Thai rice is anticipated as a result. However, while the Thai Rice Exporters Association reported in early April that rice stocks were ample, it also acknowledged difficulties in securing labor because of Cambodian workers heading home ahead of their government’s lockdown (which is now in place). These uncertainties have already pushed the price of rice in Asia to a seven-year high.

Developed countries around the world are also not immune from the effects of COVID-19 on food production. In the USA, billions of dollars of perishable food have gone to waste because of the shutdown of the food service industry. The National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition estimated that the impact could be USD $1.32billion in farm losses alone, from March to May 2020. It is a similar story in Europe, where fruit and vegetable crops in Spain, Italy, France, Germany and the UK may end up rotting in the fields because migrant workers cannot cross borders to take up farming vacancies. Some countries are calling for volunteers to help the situation.

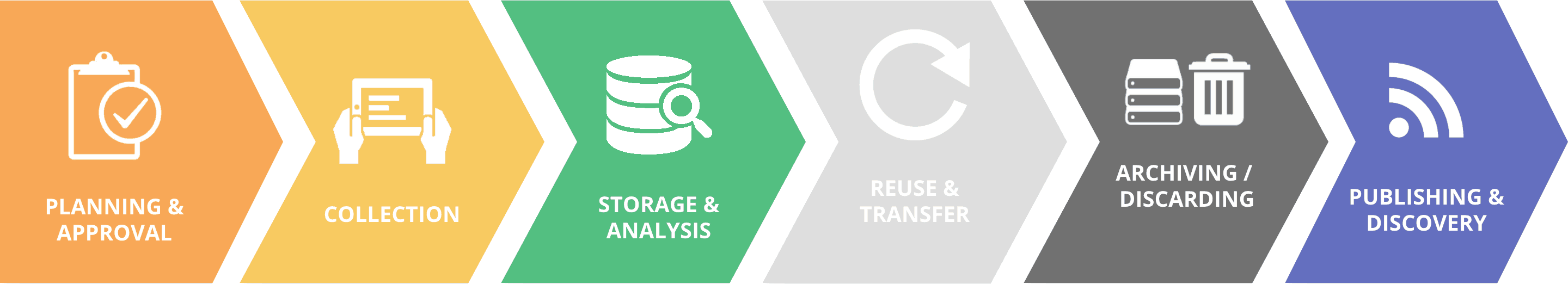

One positive amid this dire situation is that it is now possible for authorities everywhere to employ satellite technology to help them with agricultural planning. In the past, the large size of satellite image files meant processing and analysis of satellite data was limited to well-equipped and well-financed labs. However, the launch of Google Earth Engine (GEE) and advances in cloud data storage in recent years have brought the power of satellite technology and analysis to anyone with a desktop computer and internet connection. Free for non-commercial use, GEE provides environmental data from satellites including Nasa/US Geological Survey’s Landsat and MODIS technology, and the European Space Agency’s (ESA’s) Sentinel 1 and 2 satellites, as well as non-satellite data, such as climate and topography.

The satellite map at the top of this article (Figure 1) was created by scientists using GEE at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and CGIAR Research Program of Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE). It is based on an ‘Enhanced Vegetation Index’ (EVI), which shows what stage plants are at in their growth cycle. The Index was derived from Nasa’s MODIS Terra daily satellite data. Historical satellite images of crops at known stages of growth were used to help ensure accuracy of the forecast.

At a time when many researchers are unable to access their work facilities, GEE offers a way for authorities to ensure they base critical decisions around agriculture on scientific evidence. It could, for example, help them ease travel restrictions to ensure sufficient labor and machinery are in place when crops are ready to harvest. And it could assist authorities plan rotations to ensure everyone gets a turn at selling their produce at market. Critically, provided governments act quickly, the technology also has potential to stop foods from going to waste in the fields. The pandemic crisis is forcing the world to innovate. Agricultural planners and farmers must do so as well. If we can harness satellite data for this effort, we may be able to keep farmer livelihoods intact and food supplies secure.

Beta-version of the Global Crop Monitoring Tool using Google Earth Engine can be browsed here.

Thrive blog is a space for independent thought and aims to stimulate discussion among sustainable agriculture researchers and the public. Blogs are facilitated by the CGIAR Research Program on Water, Land and Ecosystems (WLE) but reflect the opinions and information of the authors only and not necessarily those of WLE and its donors or partners. WLE and partners are supported by CGIAR Trust Fund Contributors, including: ACIAR, DFID, DGIS, SDC, and others.

April 17, 2020

CGIAR-CSI