8 food security implications of the COVID-19 crisis

From disrupting agricultural input supply chains to carving out new crisis response roles for social media, the pandemic’s impacts on the state of global food security are vast and variable.

CGIAR’s global partnerships represent a critical network for diagnosing, predicting, and informing responses to food security shocks.

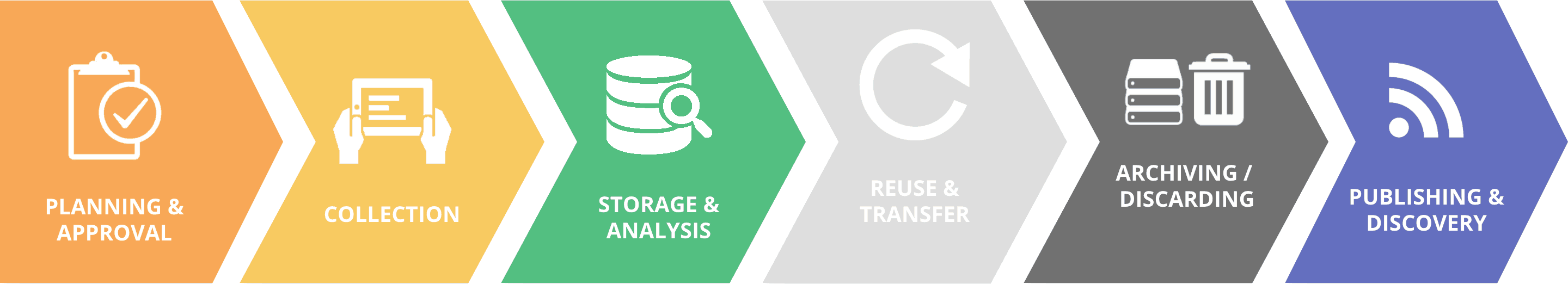

The Platform benefits from these partnerships and builds on them through open, collaborative Communities of Practice in big data research; driving open data standards and sharing; alignment with digital-first food system actors such as the Strike Two Summit, and on-the-ground digital innovation projects through the CGIAR Inspire Challenge.

These partners continue to inform and strengthen our collective sense-making as we examine the evolving food security implications of the COVID-19 crisis.

Here is what we are seeing:

- Disruption and isolation of global supply chains. The Director-General of the Food and Agriculture Organization has called on stakeholders and governments to avert unnecessary blockages to global food flows. They note that low and middle-income countries account for around a third of the world’s food trade, which provides very significant contributions to incomes and welfare and plays a critical role in global food security. Our networks and Reuters News report that these blockages are already happening worldwide, especially for perishable goods. Migrant or seasonal labor is constrained, and as a result many of the more labor-intensive crops will not get to market.

- Constraints on agricultural inputs and production: Many parts of the world are entering planting season, and agricultural input supply chains are disrupted. Again labor shortages may appear at critical points of the cropping season.

- Localization of food systems. Global and national disruption and isolation is driving localization of food systems. While localization and regionalization are important for self-sufficiency, global food flows are essential for accessible prices, global food system stability, and reaching the most vulnerable with food assistance.

- Price disruptions and signals of potential speculation. Supply of perishable goods appears particularly disrupted and to be leading to some price volatility. We have begun to see potential signals of this in commodity prices, and it could well intensify if past crises are any indication.

- Digitally-enabled firms are better equipped. Digitized enterprise resource planning, distribution, promotion, and transactions are proving to be key tools for quick localization or rapid set-up of digital commerce. Enterprises of all sizes that do not have these in place are being hit harder by the crisis.

- High-frequency monitoring data are critical. Our existing systems for monitoring prices, crop health, movement of goods and people, consumption, and the supporting natural resources and ecosystems are still insufficient for enabling the living, dynamic sense-and-response capabilities we need to mitigate the effects of the crisis on food systems and equip them for long-term resiliency.

- The recovery may not be “V-shaped.” In the near term, economic activity will likely “walk” rather than “run” as the crisis subsides, leaving broken supply chains, disrupted payment networks, and several industries struggling to return to previous levels for years to come.

- Social media are influencing behavior and accelerating new means of intermediation. Trusted social networks are critical for navigating crises, and social media—much maligned for being a vehicle for disinformation—is also part of the solution. Trusted digital networks can help fill the gaps for connecting supply, consumption, price information, and labor in new ways.

These observations are imperfect snapshots of an evolving situation, but they are the basis for continual learning as we target our responses.

The whole of CGIAR is pivoting its 2020 plans towards response, recovery, and long-term resiliency of global food in light of the COVID-19 crisis.

The Platform for Big Data in Agriculture is supporting that effort, leveraging its cross-cutting, big-data enabling, and partnership role within CGIAR as we work together towards recovering and (re)building resilient global food systems.

Feature photo credit: The Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT.

April 23, 2020

Brian King

Platform Coordinator

CGIAR Platform for Big Data in Agriculture

Cali Colombia

44 - 44Shares

Latest news

44 - 44Shares