Taking sustainable farming practices to the last mile

This blog is a submission to the Community of Practice on Data-Driven Agronomy’s blog competition on digital extension—an opportunity for those working in the digital extension in agriculture field to share their experiences with their technologies, business models, key challenges, and major bottlenecks, as well as how they solved such challenges, when creating and implementing innovative solutions.

“A community that learns together excels together. We need to form communities that learn together.” We also need communities that act together. In the quest for higher yields by the indiscriminate use of chemicals, we are missing precious nature’s jewels like bees, earthworms, and healthy soils. We believe that natural farming is a way that helps in living and working in harmony with nature.

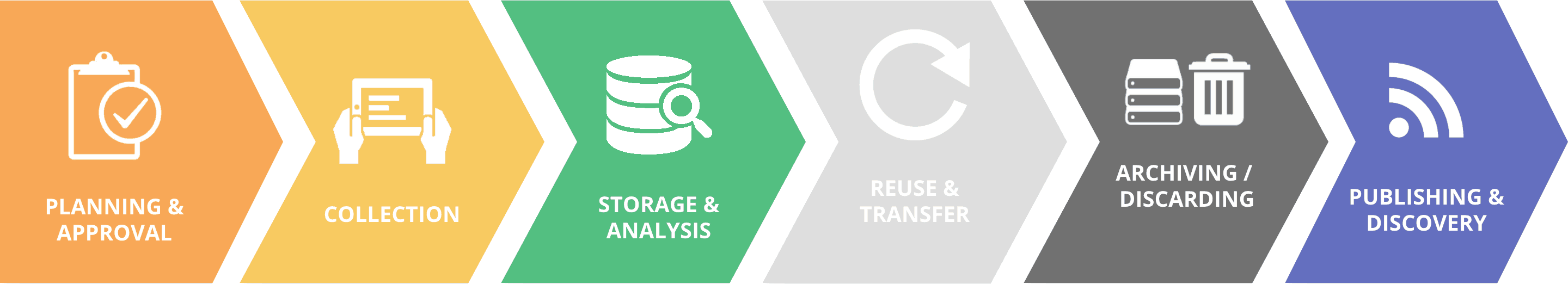

Andhra Pradesh Zero Budget Natural Farming (APZBNF) Programme, initiated by the state government of Andhra Pradesh, India, is working to achieve this by shifting six million farmers to chemical-free and eco-friendly farming practices. However, it is not easy to transition from the conventional agricultural practices that have been carried out for decades to agroecology-based farming.

This is where digital extension plays a role in taking these sustainable farming practices to the farmer in the last mile. As times are changing, extension methods are also evolving and becoming equipped with the latest technological advancements in the form of digital extension services.

APZBNF uses a combination of practices properly blended with technology and human mediation to provide better extension services. Video mediated extension is one of the core principles of the APZBNF extension system. More than 500 videos are produced on various topics, beginning with input preparation to post-harvest management of diversified crops cultivated in Andhra Pradesh. Videos about the success stories of progressive farmers are also produced. The question is who produces the videos and how it reaches the farmers.

APZBNF follows the participatory video approach where the video producers and actors are from the community. Farmers turned Video Resource Persons (VRPs) who are members of the community are trained by professionals to produce the videos and feature people from their villages. For every cropping season, there will be a schedule to produce the required videos based on demand and reviewed by the committee before sending it for dissemination. The videos will be screened with the help of pico projectors by the Community Resource Persons (CRPs) who are Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) farmers who facilitate the discussion followed by the screening. Usually, the screening will take place during the evenings in the premises of the common spaces in the village. In addition to this, we are screening the videos in the Women Self-Help Groups (SHGs) meetings which act as a catalyst for the desired change.

Community Resource Persons have a provision to enter the details like the name of the video screened and number of participants in an android-based mobile application, and this data, combined with other data collected from the field, will be used to make better decisions and generate more relevant content for the farmers. By involving local institutions in this process, the community owns the entire transformation process.

What are the biggest challenges you have faced? How did you overcome them?

We came across various barriers during the initial stages our journey towards a sustainable change. Building local capacity to take this movement forward is crucial. Identifying persons from the farming community who are not familiar with the camera or any other electronic gadgets is a difficult task. After a series of workshops, we were able to shortlist a pool of potential persons for video resource persons and trained them in video production and editing with the support of Digital Green Foundation. To make this process cost-effective and affordable we have opted for open-source editing tools instead of proprietary software. The selected candidates are deployed across 13 districts of Andhra Pradesh to work in coordination with the District Project Management team. They produce videos which cater to the farmers’ needs.

The next challenge is how to produce the videos and whom to feature. To make the video an effective tool, we use a participatory process with local communities to whom the audience can connect easily, giving better results.

Additionally, it was not easy for the farmers to face the camera and explain the input preparation process. Our VRPs and Community Resource Persons played a prominent role in making the farmers comfortable in front of the farmers which increased the video quality.

It sounds easy to upload all the produced videos on an online platform and ask the farmers to watch on their mobiles or other devices. However, in reality, there are several infrastructure hurdles to implement this as the internet connectivity in the last mile does not allow for video streaming. Additionally, not all the clientele have the technological skills to make this possible.

We have chiseled out a way to deal with this by opting for portable (pico) projectors which are available at the community level and operated by Community Resource Persons. Because CRPs have varying levels of education and familiarity with these technologies, the key lies in building local capacity.We yielded results by investing in capacity building sessions and workshops at different levels.

Local ownership of the process makes this model sustainable, and policy and infrasturcture support from the state government helped scale up the programme.

In your opinion, what is the main opportunity for digital extension services? What recommendations would you make in order to realize this opportunity?

In this data-driven world, digital extension services play a big role in bridging the gap between scientific research and farmers’ needs.

Digital extension services have the power to widely disseminate content in local languages and provide end-users with offline access to the content.

Recent technological advancements have paved the way for access to diversified data. Soil and weather data is empowering and should be transferred to the clientele in a consumable form in order to build the local knowledge base.

***

Photo: Prashanth Vishwanathan / CCAFS. 27 year old Vinod Kumar (L) and his wife Ruby Mehla recieve regular updates on weather and climate smart practices through voice messages on their registered mobile phone in the Climate Smart Village of Anjanthalli, Karnal State, India.

Click here to view the full list of articles competing in the digital extension services blog competition.

January 20, 2020

Veerendra Jonnala

Project Executive - ICT

Andhra Pradesh Zero Budget Natural Farming (Rythu Sadhikara Samstha)

Latest news